Brandon Sanderson is a prolific author of modern fantasy, renowned especially for his ability to design deep and interesting magic systems. Over the course of his career, he has developed a series of “Laws” that govern his philosophy on magic design and worldbuilding.

In this article, we will break down his advice and explore how it can be applied to the writing and running of a TTRPG as a Game Master.

What are Sanderson's Three Laws of Magic?

We'll begin with a summary. The three laws are:

- An author’s ability to solve conflict with magic in a satisfying way is directly proportional to how well the reader understands said magic.

- The costs, limitations, and flaws described in your story are what make your magic interesting.

- Before adding something new to your system, first expand on what you already have.

Now let's dive into each one, and see how they might be applied to TTRPGs.

Sanderson's First Law of Magic - On Consistency

“An author’s ability to solve conflict with magic in a satisfying way is directly proportional to how well the reader understands said magic.”

It should, as often as possible, be clear to your readers how and why magic is applied to solve problems in your story. Note the key phrase: “in a satisfying way.” Your ultimate goal as a Game Master is to provide your players with a coherent and consistent world, and any feat of magic used in your world should adhere to the rules as understood by your players.

Sanderson describes this as “internal and external consistency.” Internal consistency means that the internal logic of your story fits and is consistent with itself - no event or action within the narrative should contradict another. External consistency means justifying why things happen in your story to a person who understands the laws of our universe. As an example of leveraging our shared understanding, consider Marvel’s X-men. X-men have mutant powers because they carry the X-gene. This concept relies on our shared understanding of biology in the real world.

TTRPG players will notice any deliberate violation of a game’s internal or external consistency. If they think something is unfair, if they feel the hand of the DM tampering with the internal logic of the world, it will pull them out of the world and disrupt the flow of the game.

Let’s look at an example of these principles in action. Say you’re running a game of D&D, and the party encounters the evil wizard that you want to use as a recurring villain. You have him teleport away - but you forgot that a member of your party has counterspell. They roll a natural twenty to intervene.

An unprepared or inexperienced DM might panic, stammer for a moment, and simply say, “it doesn’t work,” or, “he disappears before you can finish casting.” This is an unsatisfying solution that defies the rules that govern your game. Instead, have your wizard use a counterspell of their own. The result is the same, but this way you adhere to the logic of the world. The players may be irritated that their enemy escaped, but they won’t feel that the rules of the world have been violated just because things weren’t going the DM’s way.

Sanderson's Second Law of Magic - On Costs

“The costs, limitations, and flaws described in your story are what make your magic interesting.”

These limits, Sanderson argues, are more interesting and carry more narrative and dramatic potential than the powers themselves.

Costs in Magic Systems

A cost is a penalty for using magic. The costs are known by the magic users and willfully paid.

The concept of cost is evident in the Wheel of Time. The One Power is potent and fantastical, but it is tainted. It causes its wielders to rot from within, falling inevitably into madness. This cost creates a dramatic tension that underlies each decision to use the Power.

In the Call of Cthulhu TTRPG, players risk losing Sanity every time they engage with the system’s eldritch magic. Sanity is a statistic that is very hard to replenish, and that dwindles faster the more of it you lose.

Limitations in Magic Systems

While a cost is a deliberate penalty taken on by an actor, a limitation is a penalty that can’t be changed or avoided, and must simply be accepted.

Superman’s powers are limited by the mineral Kryptonite, for instance. Kryptonite is a kind of narrative equalizer, stripping Superman of his superpowers and forcing him to confront threats on their terms. To a wizard in Dungeons and Dragons, their spell slots are a limitation. If depleted, they become much more vulnerable and have to radically change their tactics in order to solve problems.

Flaws in Magic Systems

A flaw is a deficiency that can be fixed or changed. This can be a flaw in a character, or in the world itself. Flaws provide your story with a clear direction - a problem that must be solved for the narrative to move forward.

In Elantris, the world’s magic suddenly stops working, and the characters must figure out why. Perhaps a character in your game suffers from a curse or ailment that limits their powers, and they must seek out a solution to unlock their true potential. For instance, your D&D Bard draws the ire of a hag and is cursed to suffer damage every time they tell a lie. Your character now has a clear course - confront the hag to lift the curse.

Sanderson's Third Law of Magic - On Focus

“Before adding something new to your system, first expand on what you already have.”

A proven principle of writing and design: more is not always better. Skyrim boasts almost 200 dungeons, but players often complain that these dungeons lack variety, depth, and complexity. You will better capture your players’ attention and imagination by presenting a few deep and unique elements, rather than a vast quantity that are lacking in quality and specificity.

As a Game Master, you’ll have ideas for features, elements, and abilities beyond what’s provided in a system’s ruleset. But instead of creating a brand new system, seek to expand and enrich what already exists.

DnD 5e’s experimental Mystic class serves as a cautionary tale against this kind of over-design - what started as a simple concept for a new class spiraled into a bloated, 28-page Frankenstein’s Monster that designers tried and failed to graft onto the game’s existing ruleset. If you’d like to learn more, Gamerant breaks down the case of the Dungeons & Dragons Mystic Class in this article.

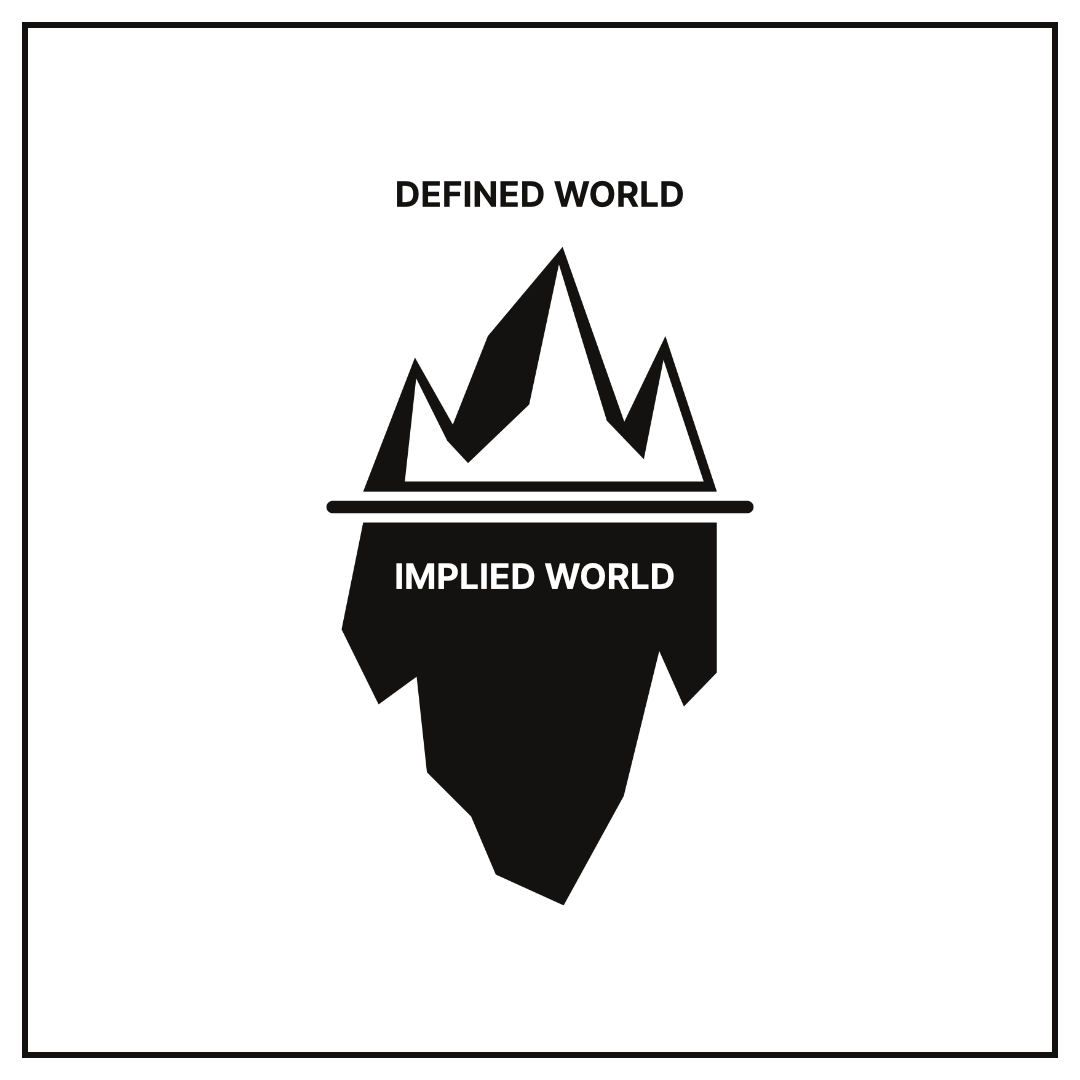

When designing a session or setting, Sanderson encourages us to think of our world as a hollow iceberg. The tip of the iceberg is the worldbuilding that is explicitly explained and defined. The rest of the iceberg is the worldbuilding that is assumed by the players or implied by the DM but not expressly defined.

A DM only has so much time to dedicate to worldbuilding, and can’t be expected to painstakingly design an entire universe. You should only design what’s necessary for your game and its story. You can still hint at further details, which helps weave an illusion of a deep and living world that convinces your players. This is the “hollow iceberg” theory of world design.

Sanderson's Zeroth Law of Magic - On Having Fun

Sanderson has one more piece of advice, which he likes to call his “Zeroth Law.”

“Always err on the side of what is awesome”

When in doubt, start with your most exciting idea and work backward from that to incorporate it into your world. Seek to make the most interesting, awesome version of your world you can.