Tabletop campaign stories aren’t told in a vacuum. They need to be grounded in a world for the players to respond to. Whether the call to action comes from a kingdom at war, a village plagued by mysterious disappearances, or anything else your imagination can conjure up, the stories of your worlds are integral to the stories of the characters who interact with them. This makes worldbuilding an essential skill for any Game Master to develop.

Building an entire world from the ground up is a daunting task - but it doesn’t have to be! In this article, we’ll explore author Brandon Sanderson’s approach to worldbuilding and how to apply it to your own games.

Table of Contents

- Where do I start with worldbuilding?

- Convey information about your setting through dialogue

- Concrete VS Abstract Worldbuilding

- Show, Don’t Tell: Example for Game Masters

- How much worldbuilding is too much?

- Continuous, Collaborative Worldbuilding

- Our Summary of Brandon Sanderson's Worldbuilding Tips

Where do I start with worldbuilding?

The first question any GM should ask themselves when building a setting from scratch is where do I start? That’s a reasonable question! It’s a lot of work. When GMs pour their hearts and souls (and time) into extensive worldbuilding only to discover that their players aren’t as excited by it as they are, it’s a recipe for discouragement and burnout. Thankfully, we can avoid wasting our time by following Sanderson’s tips for building just as much world as we need for the story.

Sanderson states that the purpose of worldbuilding is to enhance the story that you are trying to convey—and while the setting defines the story being told, it is paradoxically the least important part of it. In fact, the most engaging stories are ones that focus on creating interesting characters first. After that comes the plot, and only then do you consider what kind of setting will serve those best. To reiterate, here's the recommended sequence when worldbuilding:

- Develop interesting characters

- Map out the plot

- Design the setting to serve the characters and the plot

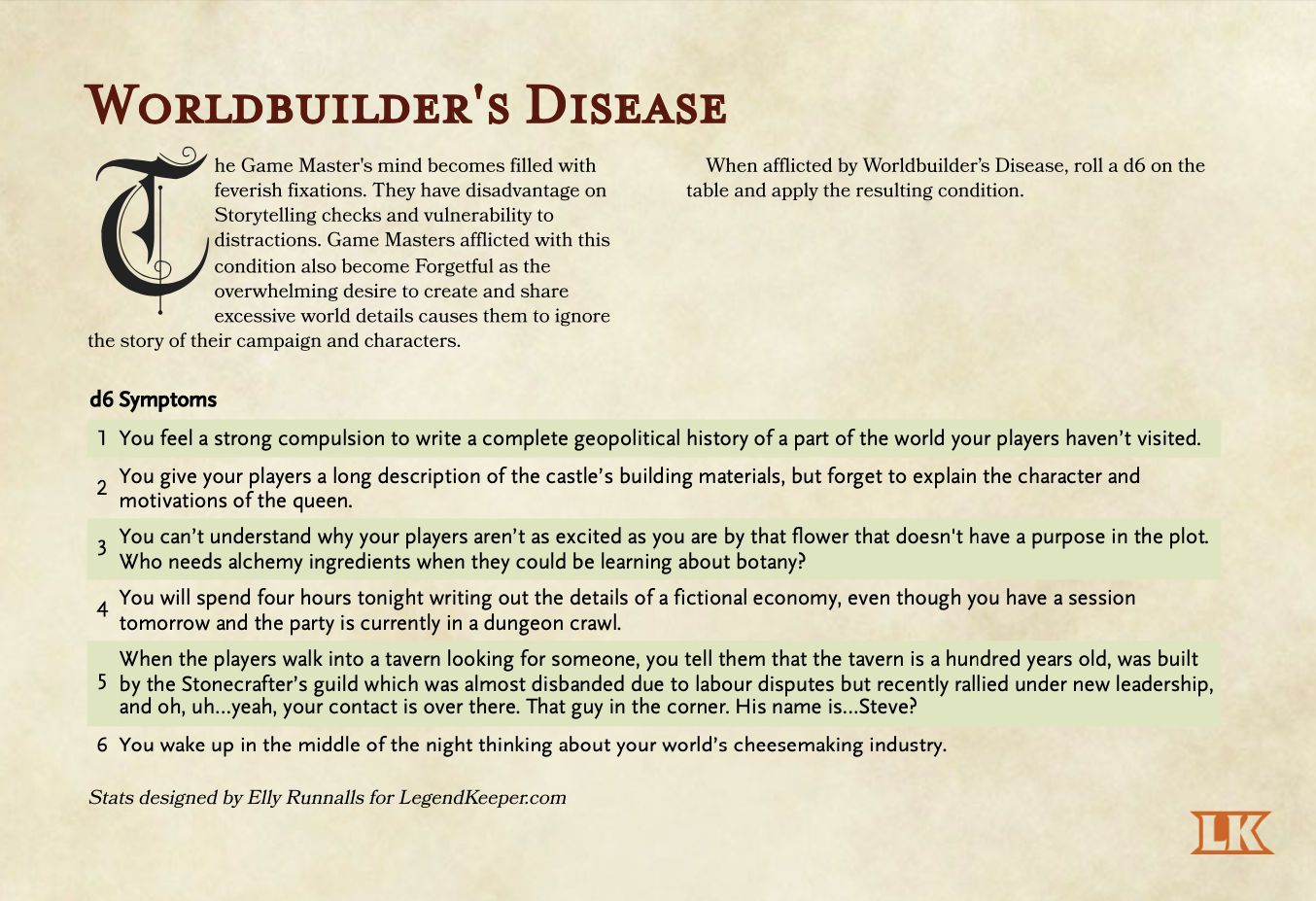

How to avoid Worldbuilder's Disease

Let’s say you want to write a campaign in which the PCs are tasked to help or hinder a rebellion against the queen. Who the PCs are helping, and why, are the hooks that are going to draw them into your game and give them a reason to explore your world.

Once they know that the leader of the rebels was once part of the queen’s inner circle and is fighting from the shadows until she has enough support to stage a coup, then the setting becomes important. The size of the kingdom, its relationships with neighboring kingdoms, how its social classes are divided, its dominant cultural practices — all those things only become meaningful after the players have a reason to care about the people who live there.

The danger is what Sanderson calls “Worldbuilder’s Disease” — a common struggle for authors and GMs alike. Worldbuilder’s Disease is what happens when you become so enthralled by the world you are creating that you never get around to creating the story. Your setting becomes more fascinating to you than what takes place in it. This is where so much discouragement and burnout takes root.

Let’s continue with our example of the PCs getting involved in a rebellion against the queen. It is important in that story for the PCs to know whether a neighboring kingdom is sympathetic to the queen or the rebels. What they don’t need to know is a detailed explanation of that kingdom’s history, economy, or architecture.

I understand that going down rabbit holes can be a lot of fun. But in a TTRPG campaign, those details will only get in the way unless they are relevant to the story.

Convey information about your setting through dialogue

With all that in mind, how do we approach worldbuilding in a way that serves and enhances the story rather than obscuring it? Sanderson believes that the “grand skill” of writing science fiction and fantasy is learning how to convey information about your world in a way that is interesting. Conveying information through long blocks of detail-heavy narration is not interesting. Sanderson shows us a better way.

Sanderson encourages giving information through dialogue as much as possible. In TTRPGs that translates to interactions between PCs and NPCs. When I come to the table as a player, I want to experience the GM’s world through the story being told, the perspectives of the characters who inhabit it, and by seeing how different elements of the world impact them. This circles back to the characters being more important than the setting when it comes to engaging your players. Let’s look at an example:

Example A: The Information Dump

“Things have been tense in the city ever since Queen Jorlanna enacted a new law cracking down on criticizing the crown. Moira Vathirond, the former soldier who used to hand out leaflets in the square, has been arrested. The elven bard Kessler used to tell satirical stories at the most popular tavern in Fairhaven District every night. Now he only performs once a week in the back room. He’s 400 years old and has seen more than a few rulers come and go. He even fought against the queen’s great-grandfather!”

This is the kind of info dump Sanderson advises against. It’s packed with impersonal information and details. The players don’t know yet who Moira or Kessler are, or why they should care.

Example B: Making it Personal

“Newcomers, huh? Best advice I can give is to be careful who you share your opinions with. People are being arrested in the streets for speaking out against Queen Jorlanna, and even old Kessler at the Silver Tankard hardly dares to spin his stories anymore for fear that they’ll be taken the wrong way. I can’t shake the feeling that someone is always looking over my shoulder waiting to rat me out.”

Notice the difference? The NPC is conveying fear and a personal stake in the situation while planting the hooks for the players to pursue more information about the arrests or Kessler.

When you give your players space and motivation to pursue more details for themselves, you give them room to actively engage with the story and the world in a more immersive way.

Concrete VS Abstract Worldbuilding

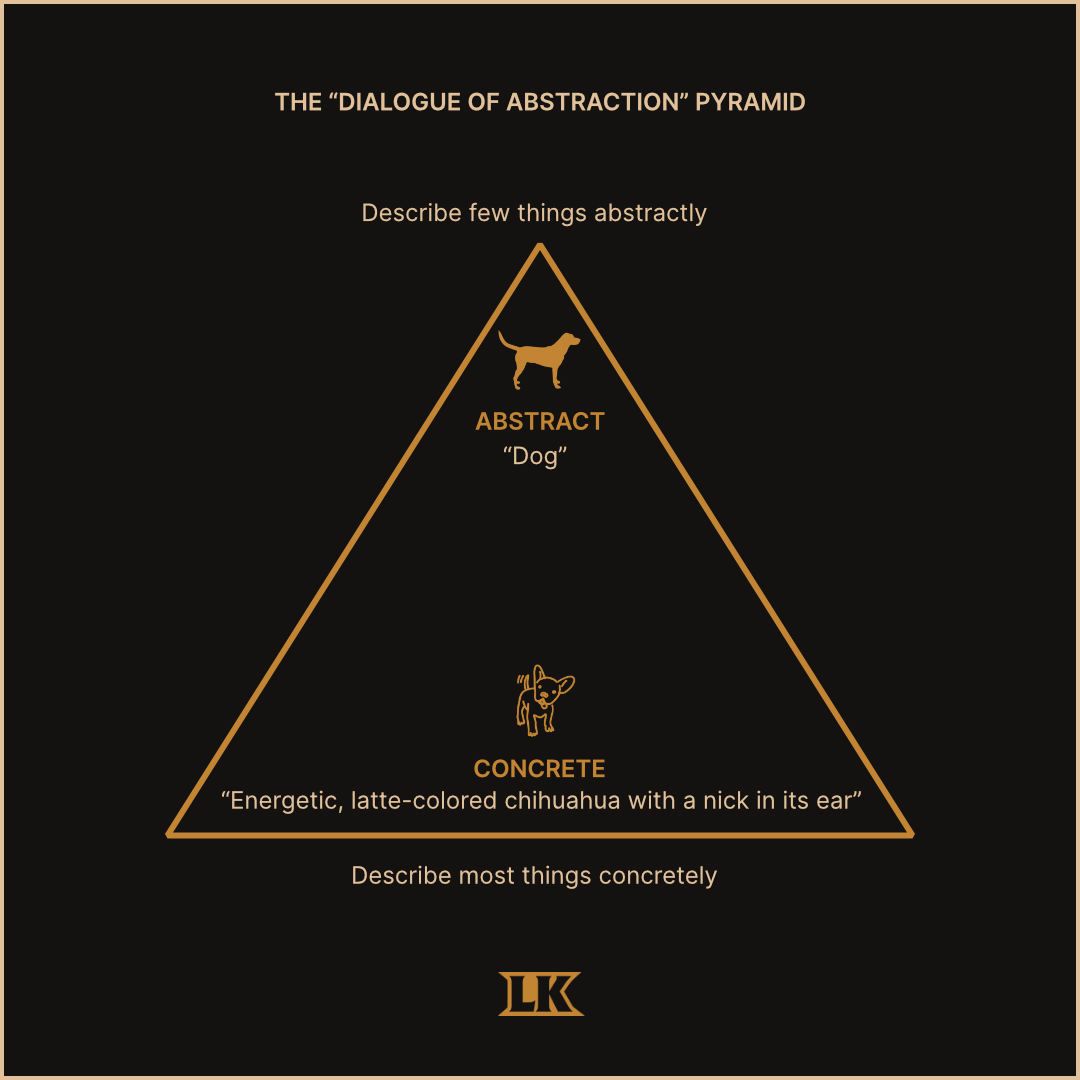

When deciding which details to add to a scene, it’s important to use meaningful descriptors that point your players toward concrete concepts instead of abstraction. Sanderson visualizes this “dialogue of abstraction” as a pyramid. At the bottom of the pyramid is concrete language that is simple, straightforward, and leaves the least amount of wiggle room for your players to interpret that information in multiple ways. That foundation is where the majority of your worldbuilding should take place.

Although the goal is to be concrete, I often find it easier to start at the top of the pyramid and work my way down. Let’s say I want a dog in my encounter. If I tell three players they see a dog with no other information, they’ll have three different ideas about it. The idea of “dog” is at the top of the pyramid.

Now tell the same three players that they see a skinny brown terrier with a greying snout and a nick in its left ear, and the abstract concept of a dog has become a concrete foundation for all the players to work off of.

Show, Don’t Tell: Example for Game Masters

One of the best ways of conveying worldbuilding information is by showing that information to your players rather than telling them about it. Sanderson suggests showing your world to your players by putting them in situations where they want something that they are being prevented from having, and letting them work proactively to get it.

If the PCs have a quest to go to the Silver Tankard and get information from a local criminal, the quest-giver (a.k.a. you) telling the party all about the bartender, the patrons, and the secret backroom removes the opportunity for the players to experience the Silver Tankard when they actually get there. When you show your players your world through the eyes of the characters who inhabit it, that is when details become meaningful to them.

How much worldbuilding is too much?

When deciding how much information to create for your world, Brandon Sanderson strongly encourages focusing on one physical element and no more than two cultural elements.

Start by breaking the world down into two parts: the physical setting, and the cultural setting.

- The physical setting is comprised of all of the things that would exist in your world whether or not it was inhabited by sapient beings. This includes things like climate, flora and fauna, terrain, and innate magic.

- The cultural setting is comprised of the parts of the world that were created by sapient beings, and portray or define their interactions with each other. This includes things like religion, social hierarchies, government, gender roles, history, fashion, language, and taboos.

All of this is a lot of information to pack into one story. Focus on one physical setting and no more than two cultural elements. Within that physical setting, you should narrow your focus even further to information that is directly relevant to your characters and story.

My favorite published campaign setting, Eberron, is made up of multiple physical settings (countries and landmasses) which all have their own distinct cultural settings. But Eberron is an official Wizards of the Coast setting that has been written by numerous authors over the course of nearly twenty years for a broad audience.

Your world’s audience is your players, and limiting yourself to one physical setting and two cultural elements will give you more time and energy to focus on the details that matter to the story you and your players are telling together.

Continuous, Collaborative Worldbuilding

Worldbuilding should be fun.

If it’s starting to feel like a chore, put it aside and work on writing what excites you. Focus on telling the story you want to tell, and let the worldbuilding elements fall into place later. It is okay to not have all the details of your world fleshed out from Session 0! As your campaign’s story emerges and changes in ways you never saw coming (because no plan survives contact with the dice — or the players), retroactively adding elements to your world is a natural progression.

Reacting to in-game moments also gives space for your players to join you in worldbuilding. I absolutely love it when I ask a GM for more details about the tavern I’m in and they ask me to describe what my character sees instead. Not only does this take some of the work off your shoulders, it makes your players more invested in the game. It also gives you information about what kinds of world details they are interested in.

Worldbuilding is a storytelling tool, and the story belongs to everyone at the table.

Our Summary of Brandon Sanderson's Worldbuilding Tips

Worldbuilding can be overwhelming, but it doesn’t have to be! Using Brandon Sanderson’s worldbuilding principles, creating your own world for a tabletop campaign can be a fun, satisfying, rewarding exercise for both you and your players.

To summarize:

- The purpose of worldbuilding is to serve and enhance the story being told.

- Avoid “info dumps” and convey the majority of your worldbuilding information through the characters who inhabit it.

- Putting characters in a situation with a clear goal and obstacles is a great way to “show” instead of “tell” them about your world.

- Choose one physical and one cultural setting to tell your story in, and focus on developing one or two core elements of your cultural setting.

- Don’t worry about developing everything at once. You can retroactively add worldbuilding elements as they become relevant to the story.

- Inviting your players to participate in worldbuilding is a great way to increase their engagement with the story.

- Write about the things that excite you within your world and story, and have fun!

Now that you know where to start, and how to tackle this journey one step at a time, the world(building) is your oyster — and I can only begin to imagine what kinds of amazing stories you are going to tell.

Happy adventuring!

Editor's Note: This article was based on Brandon Sanderson's 2020 BYU lectures on writing science fiction and fantasy. You can watch them all for free on YouTube.